The global 3D rendering market reached USD 3.5 billion in 2023 and is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 18.2 percent through 2030. This explosive growth tells a compelling story about how far three-dimensional modelling technology has come, from simple mathematical wireframes displayed on primitive computer screens to photorealistic digital environments that rival reality itself. Understanding this evolution is not merely an academic exercise; it reveals how technological breakthroughs have transformed entertainment, manufacturing, architecture, and digital innovation across industries.

Today’s photorealistic 3D renderings are the culmination of decades of innovation, persistence, and creative problem-solving by engineers and artists who dared to imagine computer-generated worlds. This comprehensive journey traces that evolution from the earliest wireframe experiments through modern techniques like LIDAR scanning and AI-assisted rendering, demonstrating how each technological breakthrough built upon its predecessors to create the stunning visual experiences we encounter daily.

The Genesis: Wireframes and Early Computing in the 1960s

The history of 3D modelling begins in an era when computers filled entire rooms and processed data at speeds that modern smartphones would find laughably slow. In the 1960s, a revolutionary computer scientist named Ivan Sutherland created something that would fundamentally change how humans interact with machines. His groundbreaking system, called Sketchpad, demonstrated in 1963, was the world’s first graphical user interface and the first real-time interactive computer graphics system.

Sketchpad displayed simple geometric shapes as wireframes, which are three-dimensional models represented by connected lines and vertices without surface information. These wireframe representations were revolutionary because they proved that computers could display, manipulate, and transform three-dimensional objects in real-time. Users could sketch shapes directly on a computer screen using a light pen, making 3D modelling accessible in ways previously impossible.

The wireframe approach became the foundation for all subsequent 3D modelling work. Mathematically, wireframes represent objects as a collection of vertices (points in three-dimensional space) connected by edges. This simple but powerful representation allowed computers with limited processing power to display and manipulate three-dimensional models. Artists and engineers could conceptualize their designs digitally, iterate quickly, and visualize spatial relationships without building expensive physical prototypes.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, researchers refined wireframe technology. Universities and research institutions began developing more sophisticated tools for creating, editing, and analyzing three-dimensional models. The advent of vector graphics and the development of standardized coordinate systems enabled consistent manipulation of 3D geometry. However, wireframes had significant limitations: they provided no visual information about surface properties, lighting, or materials, making it difficult to judge the final appearance of a design.

The Birth of Surface Rendering and Shading Models

By the 1980s, computer scientists realized that to make wireframes appear more realistic, they needed to add information about surfaces. This led to the development of polygonal models, where surfaces are represented as collections of flat polygons, typically triangles. Each polygon could be assigned properties such as color, reflectivity, and texture, creating visual information previously impossible with wireframe alone.

The introduction of shading models was equally transformative. Rather than displaying polygons as flat colors, algorithms like Gouraud shading and Phong shading calculated how light would interact with surfaces, creating smooth gradations and realistic reflections. These shading models made three-dimensional objects appear more tangible and lifelike, even though the underlying geometry remained simple.

Material properties became editable parameters. Artists could now specify how a surface should respond to light: whether it should be shiny like metal, diffuse like cloth, or transparent like glass. This fundamental shift from pure geometry to surface properties was crucial in the evolution toward photorealism. The 1980s saw the emergence of dedicated 3D modelling software packages that made these capabilities more accessible to professional artists and designers.

Cinema’s Digital Revolution: The Game Changing Moments

While technical research advanced in laboratories and academic institutions, the entertainment industry recognized the potential of computer-generated imagery. The path to photorealistic cinema involved several landmark moments that demonstrated increasing sophistication and capability.

Early Pioneers: Tron and Computer Graphics in Film

Tron, released in 1982, was a watershed moment for computer graphics in cinema. Director Steven Lisberger and digital imaging supervisor Richard Taylor created the first major Hollywood film to feature substantial computer-generated graphics. Approximately 15 to 20 minutes of the film consisted of computer graphics, which was revolutionary for the time.

The graphics in Tron were displayed as glowing wireframes and simple polygonal shapes against black backgrounds, reflecting the limitations of 1980s computer rendering. However, the film proved that digital graphics could tell compelling stories and capture audience imagination. More importantly, it demonstrated that there was a market for this technology, inspiring studios and technology companies to invest heavily in three-dimensional graphics research and development.

The Photorealism Milestone: Jurassic Park

Jurassic Park, released in 1993, represented a quantum leap forward in cinematic computer graphics. Director Steven Spielberg and Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) created dinosaurs that audiences found genuinely believable, even though they were entirely computer-generated. The film featured approximately 60 shots with digital dinosaurs, using sophisticated 3D models with detailed surface textures, realistic lighting, and motion capture technology.

What made Jurassic Park revolutionary was not merely the volume of digital content but its seamless integration with live-action footage. The digital dinosaurs cast shadows, reflected light realistically, and moved with convincing physics. Cinematographer Dean Cundy explained that the lighting and rendering techniques used for the digital dinosaurs matched the practical lighting of the live-action scenes, creating visual consistency that felt entirely natural to viewers.

Jurassic Park demonstrated that with sufficient computational power, sophisticated rendering algorithms, and talented artists, computers could generate images virtually indistinguishable from reality. This film remains a crucial marker in the history of computer-generated imagery because it showed that photorealism in cinema was not merely a theoretical possibility but an achievable reality.

The Digital Revolution: Toy Story

Toy Story, released by Pixar in 1995, was the first feature-length computer-animated film. While the characters were stylized rather than photorealistic, the film demonstrated that entire worlds could be constructed digitally, rendered completely in computer graphics, and still captivate audiences emotionally and narratively.

Toy Story’s production revealed the enormous computational resources required for feature-length digital animation. A single frame might take hours to render on the most powerful computers available in the mid-1990s. The film’s success proved that the effort was worthwhile, and it catalyzed tremendous investment in digital animation and 3D rendering technology.

Ray Tracing and Global Illumination: The Photorealism Breakthrough

Despite the stunning achievements of films like Jurassic Park and Toy Story, significant limitations remained in how computers calculated light and shadow. Early rendering techniques like rasterization were fast but produced unrealistic lighting because they could not accurately simulate how light bounced between surfaces in a scene.

Ray tracing, also known as ışın izleme in Turkish terminology, represents a fundamentally different approach to rendering. Rather than projecting polygons onto a screen, ray tracing simulates the physical behaviour of light by tracing rays from the camera through each pixel of an image, calculating what surfaces they hit, and determining how those surfaces illuminate other surfaces.

The process works through these essential steps:

- Rays are cast from the camera through each pixel in the final image

- The algorithm determines which surfaces in the 3D scene each ray intersects

- The material properties of the surface are evaluated

- Secondary rays are cast from the intersection point to determine how that surface is illuminated

- The algorithm calculates reflections, refractions, and shadows with physical accuracy

- The final pixel color is determined by combining information from all these calculations

Ray tracing produces extraordinarily realistic images because it physically simulates light behaviour. Reflections and refractions are naturally accurate, shadows have proper penumbra (soft edges), and caustics (light patterns created by refraction) appear organically. However, ray tracing is computationally expensive. Accurate results often require tracing hundreds or thousands of rays per pixel, making real-time ray tracing infeasible on consumer hardware until recently.

Global illumination extends ray tracing by accounting for light bouncing between multiple surfaces. In real environments, light does not simply travel from a light source to a surface to the camera; it bounces among surfaces, with each bounce contributing to the final appearance. Global illumination algorithms simulate these bounces, calculating how light energy distributes throughout a scene.

The introduction of ray tracing and global illumination in high-budget productions elevated photorealism dramatically. Films like Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (2001) and Monster House (2006) demonstrated increasingly sophisticated implementations of these techniques. While early ray-traced films sometimes appeared visually sterile because the technology was still imperfect, continuous refinement and artistic development created genuinely photorealistic results.

Lidar Technology: Capturing Reality for Digital Reproduction

While rendering algorithms improved dramatically, a parallel revolution was occurring in how three-dimensional geometry itself was captured from the real world. LIDAR technology (Light Detection and Ranging) transformed the process of acquiring 3D data from physical environments.

LIDAR operates by emitting light pulses, typically in the infrared spectrum, and measuring how long those pulses take to return after reflecting from surfaces. By calculating the time delay, LIDAR systems determine the distance to each point in a scene. By scanning across an entire environment, LIDAR creates a point cloud, a dataset containing millions of three-dimensional coordinates representing the surface geometry of the scanned environment.

The benefits of LIDAR scanning for 3D modelling are profound:

- Accuracy surpassing manual measurement techniques

- Rapid acquisition of complex geometries

- Documentation of real-world environments with precise spatial data

- Elimination of guesswork in reproducing existing structures and objects

- Cost reduction for large-scale surveying projects

- Creation of detailed baselines for architectural and construction projects

In film and entertainment, LIDAR scanning became essential for visual effects. When filmmakers needed to integrate digital elements seamlessly into live-action scenes, LIDAR scanning of the actual filming locations provided precise three-dimensional geometry and spatial information. This data ensured that digital objects correctly interacted with light, cast appropriate shadows, and occupied space consistently with the physical environment.

Architecture and engineering benefited enormously from LIDAR technology. Rather than manually measuring buildings or infrastructure, professionals could scan existing structures with centimetre-level accuracy, creating detailed three-dimensional models for renovation planning, structural analysis, or digital documentation. This capability transformed workflows and made the creation of digital twins practical and economical.

Digital Twins: Virtual Models of Physical Reality

The concept of digital twins emerged as LIDAR and 3D modelling technology matured. A digital twin is a comprehensive digital representation of a physical object, structure, system, or process. Digital twins serve multiple purposes: analysis and simulation, predictive maintenance, training and visualization, and optimization.

In manufacturing, digital twins allow engineers to simulate production processes, identify bottlenecks, test modifications virtually, and predict maintenance needs before equipment failures occur. In urban planning, digital twins of entire cities enable planners to visualize proposed changes, simulate traffic flow, and assess environmental impacts before implementing physical changes.

The creation of accurate digital twins depends fundamentally on the ability to capture real-world geometry with LIDAR and other scanning technologies, then render this data with sufficient fidelity that digital twins effectively represent physical reality. The historical progression from wireframes to digital twins represents a transformation in how we conceptualize and interact with information about physical systems.

Advanced Techniques: Detroit Become Human and Mesh Technologies

As 3D modelling matured into a sophisticated discipline, game developers refined techniques specifically optimized for real-time rendering and interactive environments. Detroit: Become Human, developed by Quantic Dream and released in 2018, showcased cutting-edge techniques for creating photorealistic human characters in an interactive medium.

The game demonstrated several advanced modelling and rendering techniques:

- High-polygon character models with hundreds of thousands of polygons per character

- Advanced facial rigging systems enabling subtle emotional expression

- Physically based materials accurately representing skin, fabric, and metal

- Performance capture technology translating actor movements to digital characters

- Sophisticated mesh technologies for efficient data representation

- Real-time ray tracing for environmental lighting

The reference to mesh technology in Detroit: Become Human likely refers to advanced mesh optimization and subdivision surface techniques. Subdivision surfaces allow artists to create smooth, complex shapes using relatively simple underlying geometry. The game engine subdivides coarse polygonal meshes at runtime, creating the illusion of smooth, high-resolution surfaces without requiring artists to manually model millions of individual polygons.

This approach balances visual quality with computational efficiency, essential for interactive media where scenes must render in real-time. Artists create manageable base meshes, the engine applies mathematical subdivision rules to create finer geometry, and material properties render this geometry with photorealistic accuracy. Detroit: Become Human elevated this technique to an art form, creating human characters so detailed and expressive that they generated genuine emotional engagement from players.

The CGI Evolution and Modern Rendering Techniques

The evolution of CGI (Computer-Generated Imagery) can be traced through landmark technological and creative achievements. Each generation built upon previous innovations while solving previously intractable challenges:

- 1960s1970s: Wireframes and basic geometric rendering

- 1980s: Polygonal models and shading algorithms

- 1990s: Ray tracing, global illumination, and real-time 3D graphics

- 2000s: GPU-accelerated rendering and physically based materials

- 2010s: Real-time ray tracing and advanced material capture

- 2020s: AI-assisted rendering and neural rendering techniques

Modern rendering engines like Unreal Engine 5, Unity, and proprietary film production software combine multiple rendering techniques simultaneously. Deferred rendering allows efficient calculation of multiple light sources. Screen-space ambient occlusion rapidly approximates global illumination. Metallic and roughness parameters precisely control how materials respond to light.

Render farms, massive collections of computers working in parallel, enable production studios to render complex scenes in reasonable timeframes. A single frame of a modern animated film might require 100 to 500 CPU-hours of computation, meaning a single computer would take days to render. Distributing this work across thousands of computers enables completion within practical schedules.

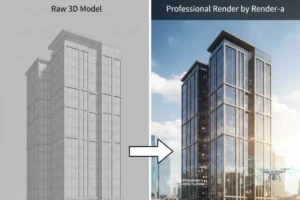

Render-a: Modern Photorealism Through Advanced Rendering Solutions

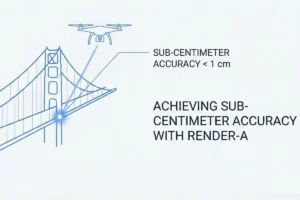

Render-a and similar contemporary rendering solution providers represent the current frontier of photorealistic three-dimensional visualization. These companies synthesize all the technological advances discussed throughout this article, combining LIDAR scanning, sophisticated rendering algorithms, AI-assisted processes, and streamlined workflows to deliver photorealistic results efficiently.

Modern rendering platforms like those offered by Render-a incorporate several cutting-edge capabilities:

- Automated mesh generation from LIDAR point clouds

- AI-powered texture inference from photographs

- Real-time ray tracing with denoising algorithms

- Material capture and recreation from real-world samples

- Interactive rendering allowing real-time adjustments

- Integrated lighting and environment simulation

- Cloud-based rendering distribution for rapid production

The integration of artificial intelligence into rendering workflows represents the latest evolutionary step. Machine learning algorithms can infer missing information from limited input data, accelerate computationally expensive calculations through trained approximations, and automatically optimize rendering parameters for desired visual outcomes. AI denoisers, for example, significantly reduce the noise inherent in ray-traced images, allowing fewer rays per pixel while maintaining visual quality.

Render-a’s approach to photorealistic rendering demonstrates how historical advances have coalesced into practical solutions. A project that would have required months of manual work by specialized artists a decade ago can now be completed in days or hours using modern tools. LIDAR data automatically generates base geometry, AI systems infer materials from photographs, and advanced rendering engines produce photorealistic results with minimal manual intervention.

The success of platforms like Render-a validates the entire trajectory of three-dimensional modelling evolution. From Ivan Sutherland’s pioneering wireframes through ray tracing breakthroughs to LIDAR-based capture and AI-assisted rendering, each innovation expanded what was possible, reduced required expertise and time, and made photorealistic visualization accessible to increasingly diverse professionals and industries.

Applications Across Industries

The evolution of 3D modelling and rendering technology has transformed numerous industries beyond entertainment. Understanding these applications demonstrates why the technological journey described in this article remains profoundly important:

Architecture and Construction

Architects use 3D modelling to visualize designs before construction, communicate concepts to clients, and plan construction sequencing. LIDAR scanning of existing structures supports renovation planning. Photorealistic renderings help stakeholders understand spatial relationships and design intent.

Product Design and Manufacturing

Manufacturers create digital twins of production facilities for simulation and optimization. Designers model products before prototype construction, reducing development cycles and costs. Photorealistic renderings facilitate marketing and client communication.

Archaeological and Cultural Heritage Documentation

LIDAR scanning preserves three-dimensional records of archaeological sites and historical structures. Digital models enable research and public engagement without requiring physical access to fragile sites. Photorealistic reconstructions help audiences understand historical environments.

Medical and Scientific Visualization

Physicians use 3D models of anatomical structures for surgical planning. Scientists create models of molecular structures, cellular processes, and astronomical phenomena for education and research. Rendering techniques make complex scientific data accessible.

Real Estate and Urban Planning

Developers create photorealistic renderings of proposed projects to communicate concepts and secure financing. Urban planners model cities to visualize proposed changes and their impacts. Virtual tours enable remote property viewing.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite tremendous progress, significant challenges remain in achieving truly universal photorealism and accessibility. Rendering complex scenes with millions of light interactions continues to demand enormous computational resources. Creating detailed, realistic textures and materials remains partially manual and requires specialized expertise.

Future developments will likely include:

- Further AI integration for automated material inference and texture generation

- Hardware acceleration enabling real-time global illumination on consumer devices

- Volumetric rendering techniques for accurate simulation of atmospheric effects

- Neural rendering approaches using machine learning to approximate rendering equations

- Democratization of tools enabling non-specialists to create photorealistic visualizations

- Integration of photogrammetry with traditional modelling for hybrid approaches

The democratization of three-dimensional modelling and rendering technology will likely accelerate. As tools become more intuitive and computational power increases, creating photorealistic visualizations may transition from specialized expertise to mainstream capability.

Conclusion

The journey from Ivan Sutherland’s pioneering wireframe graphics to today’s photorealistic digital twins represents one of the most remarkable technological progressions of the modern era. Each landmark in this evolution from wireframes to polygonal models, from Tron to Jurassic Park, from basic shading to ray tracing, from LIDAR scanning to AI-assisted rendering built upon prior achievements while solving previously impossible challenges.

The history of 3D modelling is fundamentally a history of expanding human capability. Professionals who once relied on expensive physical prototypes, expensive surveying equipment, and limited visualization methods now possess tools that exceed the computational power of yesterday’s supercomputers. Digital twins enable predictive analysis impossible with purely physical systems. Photorealistic renderings communicate complex concepts instantly across language and professional boundaries.

Modern platforms like Render-a exemplify how this accumulated technological knowledge translates into practical solutions. By synthesizing LIDAR scanning, sophisticated rendering algorithms, physically based materials, and AI-assisted workflows, contemporary rendering solutions democratize photorealism and make it accessible to industries and professionals beyond the specialized elite of visual effects studios.

The story of 3D modelling evolution is not yet concluded. Each year brings new techniques, faster hardware, and more ambitious applications. Yet understanding this history is essential for appreciating the technology underlying the digital environments, photorealistic visualizations, and interactive experiences that increasingly shape how we communicate, learn, and imagine possibilities. From wireframes to photorealism represents not merely a technical progression but a transformation in how humans visualize, plan, and understand the physical world.

Let’s Follow us: LinkedIn